A Pathway to Longer-Lasting Lithium Batteries

Just about everyone has endured the frustration of their cell phone running out of power before they get a chance to recharge, and although electric cars are growing in popularity, they remain limited by how far they can drive before their battery runs out of juice. Indeed, the energy density of batteries—how much energy they pack in a given mass or volume—has been a major challenge for consumer electronics, electric vehicles, and renewable energy sources.

New advances at Caltech may go a long way toward improving things. Researchers working in the lab of Julia R. Greer have made a discovery that could lead to lithium-ion batteries that are both safer and more powerful. Their findings provide guidance for how lithium-ion batteries, one of the most common kinds of rechargeable batteries, can safely hold up to 50 percent more energy.

Conventional lithium-ion batteries use graphite to make up the anode, the electrode at which current enters a battery cell. Graphite has been the material of choice for this task for 30 years because it is light, stable, affordable, and can endure the rigors of countless battery cycles. But there are better materials for the job, says Greer, Caltech's Ruben F. and Donna Mettler Professor of Materials Science, Mechanics and Medical Engineering, and Fletcher Jones Foundation Director of the Kavli Nanoscience Institute—if only some technical challenges can be overcome.

"Every power-requiring application would benefit from batteries with lithium instead of graphite anodes because they can power so much more," she says. "Lithium is lightweight, it doesn't occupy much space, and it's tremendously energy dense."

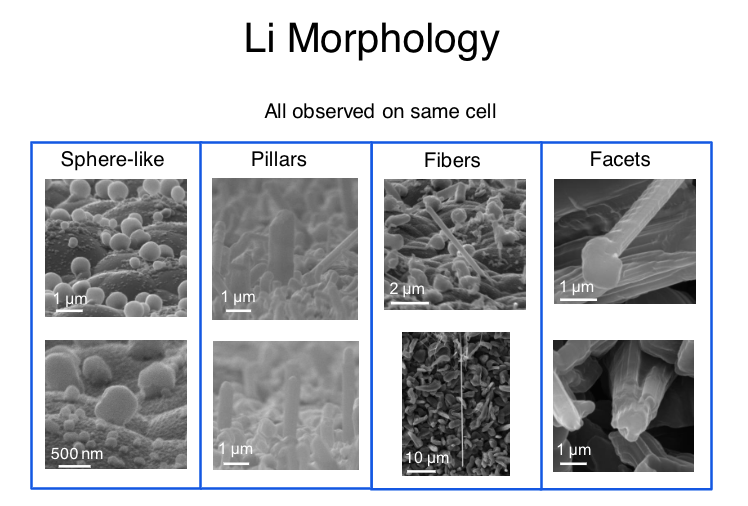

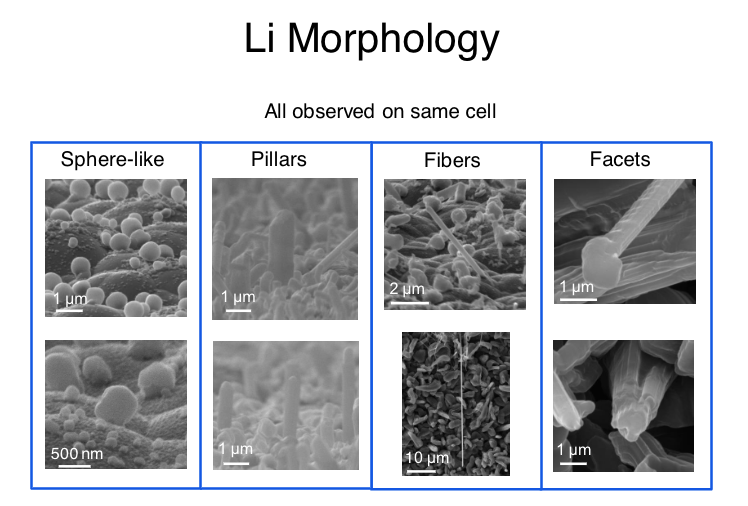

But here is the problem with lithium metal: When a battery is run through many charge–discharge cycles, the lithium naturally forms dendrites, crystals that create a kind of branching tree-like structure. During battery charging, dendrites grow uncontrollably in a lithium-metal cell and can act like tiny wires that short-circuit and kill the battery as they penetrate the system.

Researchers have long sought new ways to prevent this growth, Greer says. One possible method is to physically press something against the lithium metal to suppress the dendrites. Whereas typical lithium-ion batteries have a liquid electrolyte—the substance that separates the two battery electrodes and through which the lithium ions move—batteries that use a solid electrolyte could, in theory, apply enough mechanical pressure to hold back the dendrites.

Yet in study after study of batteries with solid electrolytes, the dendrites still grew.

Greer, who is also an affiliated faculty member of the Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute for Neuroscience at Caltech, suspected that the solid electrolytes were not strong enough to resist dendrite growth because researchers had underestimated the strength of dendrites, whose dimensions are at the nanometer scale; they lowballed it because macroscopic lithium is a relatively soft metal comparable to lead and tin. Metals, she says, can be as much as 100 times stronger at a small scale than they are at a larger scale.

"If you think of jewelry, like gold or copper, it's very malleable. You're able to easily deform it with your own hands," says Greer, who specializes in studying mechanical properties of materials at the nanoscale. "But when you reduce the dimensions of the same metals, you can get more than an order of magnitude increase in strength."

In 2015, Greer and her colleagues carved tiny pillars of lithium and tested their resilience, and found that they were at least an order of magnitude stronger than had been believed. That experimental setup did not completely reflect the way lithium dendrites behave in a real battery, Greer says. To more accurately emulate this, she and her collaborators, including Greer lab alumnus Michael Citrin and postdoctoral scholar Heng Yang, as well as Simon Nieh from Front Edge Technology, built a battery designed to grow pure lithium dendrites that are very similar to those that would form in batteries. These dendrites, the researchers found, are 24 times stronger than bulk lithium.

Julia Greer's new research demonstrates the remarkable strength of lithium at the nanoscale, where growing "dendrites" can short-circuit or otherwise damage a battery cell. (credit: Julia Greer / Caltech)

With that information, researchers now have a better idea of what is required to make a lithium-anode battery work. This represents a major research challenge, Greer says, because polymers and ceramics, the materials commonly used for solid electrolytes, both have drawbacks. Most polymers are too soft to withstand dendrite growth, while ceramics are prone to crack under the pressures exerted by dendrites.

With these new findings, scientists have a starting point. "This is as relevant to battery research as it gets, a true manifestation of how much fundamental research is relevant to technological advances," she says.

The research is described in a paper in the journal MRS Bulletin titled, "From Ion to Atom to Dendrite: Formation and Nanomechanical Behavior of Electrodeposited Lithium." Other authors include Simon K. Nieh of Front Edge Technology, Joel Berry of the University of Pennsylvania and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Wenpei Gao and Xiaoqing Pan of UC Irvine, and David J. Srolovitz of the City University of Hong Kong. The work was funded by the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) and the U.S. Department of Energy.